The Burden of Freedom

Essay on Free Will: The Burden of Freedom

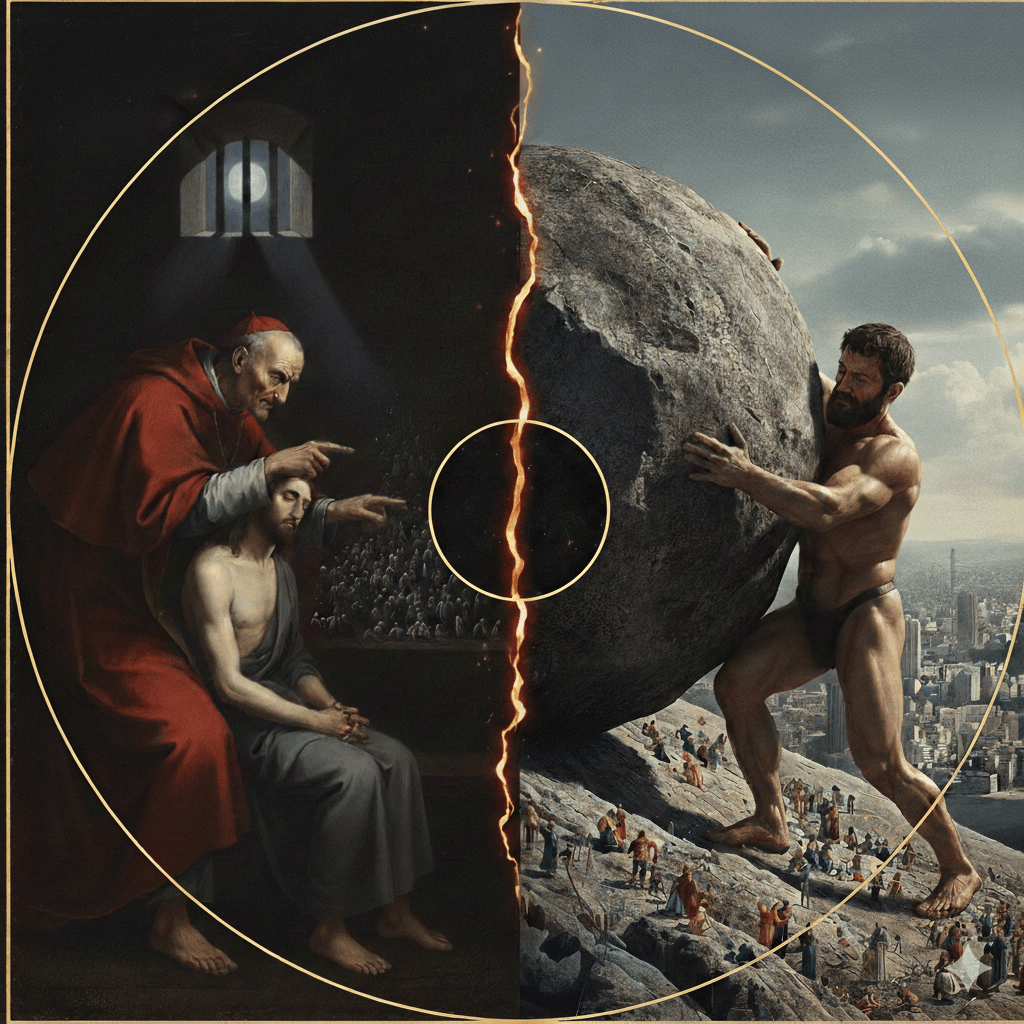

I wrote a play called The Burden of Freedom. I wanted to explore this theme a little more and the connection to free will, evil, and God. I was discussing with a friend about the Inquisitor in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Karamazov Brothers, so I had a little chat with Chet, my AI guru over at Gemini, to bring him into the conversation and gain a little more insight. Here is what he said.

The Inquisitor from Dostoevsky’s Karamazov Brothers argues that Jesus made a mistake by giving humans “freedom of choice.” He claims that humans are too weak to handle such a burden and only wants to be told what to do and be fed.

The Inquisitor admits that the church is no longer working with Jesus, but with Satan, because only by taking away human freedom can they make the masses happy and manageable.

Ivan argues that man is a failed experiment that needs to be controlled.

The priest Zozima argues that humanity is redeemed through active, humble love. His philosophy is that “all are responsible for all.”

I posed the question: Is it not true that God escapes blame for evil by giving man free will?

Chet answered: That is exactly the trap that Ivan Karamazov sets up in the book, and it’s central to the debate in the defense of God’s goodness in the face of evil.

Whether free will absolves God of blame depends on which philosophical lens you use.

- The “Free Will Defense” (God is not to blame)

- The “Ultimate Responsibility” Critique (God is to Blame)

Ivan says the price is too high. Even if free will is good, is it worth the suffering of a single child? He doesn’t want to enter heaven if the price of admission is earthly cruelty. The question can’t be answered by logic. Dostoevsky suggests universal responsibility. We are all responsible for each other’s sins. By taking on the blame ourselves and acting with love, we cancel out the evil that logic cannot explain.

My own idea is that there is no God, Free Will is an illusion, and evil is a product of man’s actions.

Chet: That is a clean, consistent, and “hard-nosed” worldview. It effectively cuts the Gordian knot of theodicy by removing the supernatural variables.

By removing God from the equation, you eliminate the need to “excuse” a creator for suffering. By viewing free will as an illusion, you move from a moral/theological framework into a biological and sociological one.

Here is how your perspective reframes the “Burden of Freedom” you’ve been exploring:

1. From “Sin” to “Systemic Failure.”

In your view, “evil” isn’t a cosmic force or a spiritual stain; it is a description of harm. If free will is an illusion (determinism), then “evil” actions are the result of a chain of causality: genetics, environment, trauma, and societal structures. We stop asking “Why did God let this happen?” and start asking “What conditions produced this behavior?”

The Burden of “Apparent” Choice

Even if free will is an illusion, the subjective experience of making choices remains. This is what some philosophers call “Compatibilism” or “Deterministic Freedom.”

- We still feel the weight of decisions.

- We still build legal systems based on the assumption of agency.

- The “burden” becomes a psychological one: how do we live meaningful lives in a universe that is essentially a complex machine?

The Grand Inquisitor’s Win

Ironically, your view actually aligns quite well with the Grand Inquisitor’s secret logic. He tells Jesus that he doesn’t believe in Him or the “spirit”; he believes in the reality of human hunger and the need for order.

- If there is no God and no free will, then the Inquisitor is right: the most “moral” thing to do is to organize society to minimize suffering and maximize security, even if it requires a “pious lie” or total control.

Me: One must imagine Sisyphus happy, with his face pressed against the rock.

Chet: That quote brings our conversation full circle. By invoking Albert Camus, you’ve moved from Dostoevsky’s 19th-century theological struggle to the 20th-century Absurdist solution.

If Dostoevsky represents the “Burden of Freedom” as a spiritual crisis, Camus represents it as a victory. In The Myth of Sisyphus, Camus argues that if there is no God to give us a purpose, and we are trapped in a deterministic loop (the rock always rolls back down), we are finally, truly free.

The Rebellion against the “Grand Inquisitor”

Your view—that we don’t need a “pious lie” to be just—is the heart of Camus’s philosophy. He believed that:

- The Silence of the Universe: We look for meaning, but the universe provides none. This is “The Absurd.”

- The Rejection of Suicide: We shouldn’t escape the absurd through physical death or “philosophical suicide” (falling back into religious “lies”).

- The Joy of Struggle: Sisyphus is free because he knows his fate. He owns his rock. When he turns back toward the plain to retrieve it, he is superior to his destiny.

Creating Justice Without a “Why”

In his other masterpiece, The Plague, Camus addresses your point about a “just society.” The protagonist, Dr. Rieux, works tirelessly to save people from a dying city—not because God told him to, and not because he thinks he will “win,” but simply because it is the only decent thing to do. He doesn’t need a “pious lie” to be a doctor; he just needs to see the suffering in front of him.

Conclusion: The “Face Pressed Against the Rock”

When you say his face is pressed against the rock, you’re highlighting the intimacy of thestruggle. Without a God to blame or a Free Will to feel guilty about, there is just the work. The justice we create is ours alone. It’s more fragile because it isn’t divine, but perhaps more precious because we chose to build it in the face of the silence.

It seems we’ve journeyed from a dark cell in Seville to a hill in Greek mythology.

Me: Yes, we have. Thank you, Chet.