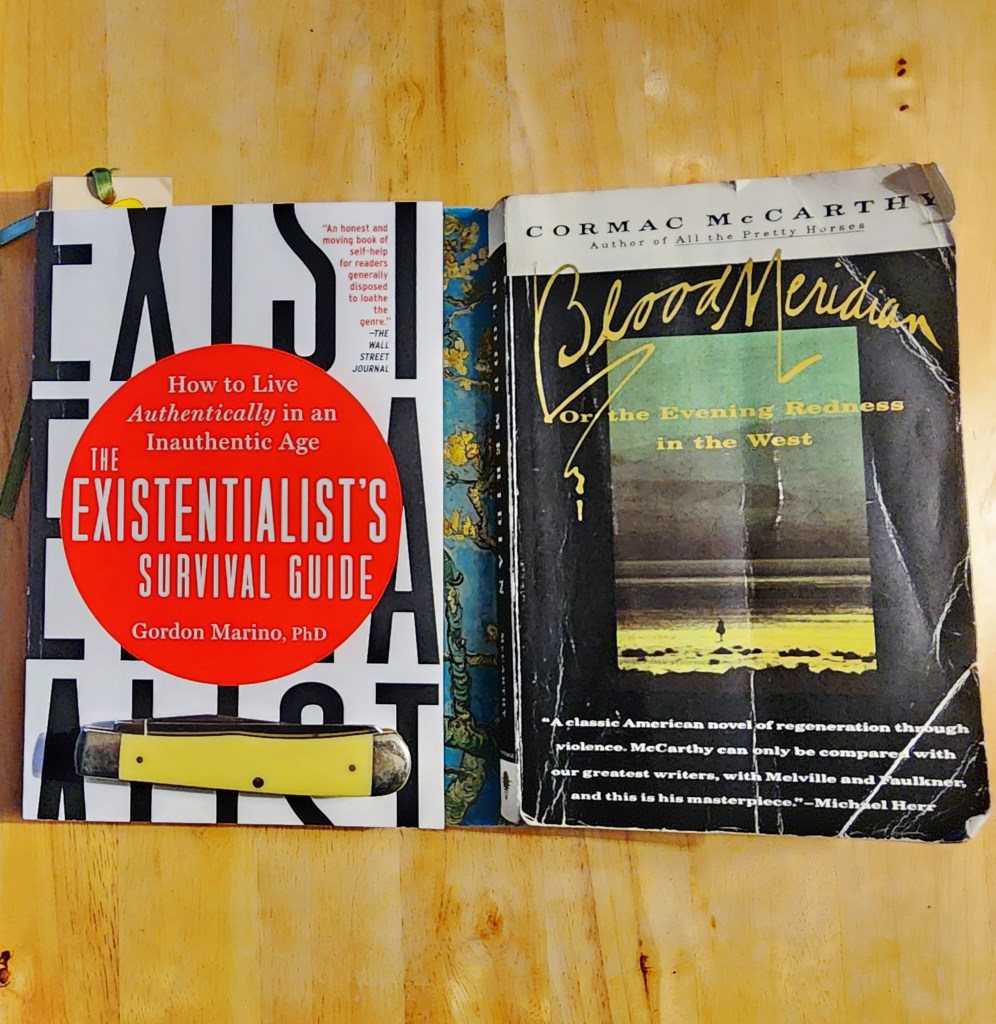

The Existentialist’s Survival Guide – How to Live Authentically in an Inauthentic Age by Gordon Marino, PhD. It is a pretty good book on existentialism. I was a little skeptical at first because the author writes through the lens of Soren Kierkegaard. It’s not that I don’t like Kierkegaard; it’s that Kierkegaard doesn’t particularly resonate with me like the other existentialists. Not to worry, there were heavy doses of these other authors that I like, like Albert Camus, Jean Paul Sartre, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

As a matter of fact, he checks all the boxes of some of my favorite authors, with mentions from the works of Camus: The Fall and The Stranger. Sartre: Nausea, No Exit, and Being and Nothingness. Dostevsky: Notes From Underground. These books are the touchstones of my life, and I was grateful for their inclusion.

Finally, this book was well written with many anecdotes from the author’s colorful past to illustrate his points and help inform the reader. It is more than just a self-help book. It is indeed a survival guide for living authentically.

Reading Blood Meridian for the second time, I picked up a lot that I missed the first time around 20 years ago. 20 years ago, when I first read it, I could not believe my eyes at what I saw on the page. I literally could not put the book down. I carried it with me everywhere I went until I finished reading it. In the intervening years, I read every other book Cormac McCarthy ever wrote. He is unquestionably one of America’s finest writers.

Blood Meridian shocks one’s consciousness with its scenes of violence and haunts the imagination with its vivid descriptions of the Old West in Mexico and Texas.

Thematically, it is about the primacy of violence. The nature of good and evil, and fate vs. agency. The story follows a character known as “the kid,” who joins a group of scalp hunters known as the Glanton Gang. They are hired by the Mexican government to hunt down Apache Indians and collect their scalps for a bounty. They soon descend into madness as they stop distinguishing enemies from foes and start slaughtering everything in their path.

Another character in the gang is Judge Holden, who may or not be the devil. His philosophy is “War is God,” and combat is the ultimate truth. He refers to “the dance” by which he means a commitment to violence and the will to power. If you aren’t dancing, you aren’t truly alive.

The kid has a spark of mercy in him, and the judge views him as his natural enemy. The final confrontation takes place in an outhouse. What happens there is not mentioned but the reaction of those who look inside would suggest something awful.

Blood Meridian is not for everyone, but it is a masterpiece of storytelling, somewhere on the level of Moby Dick. It is the telling of the end of the Old West and the beginning of the New and so-called civilization.